Now that we have broken down the running game with last week’s post, this post is going to take a look at the passing game. We will look at the passing game by analyzing the Passing Heat Map (I will admit that I stole the idea of this post when I was reading this great article posted on Grantland). A heat map is a visual representation of data that we gather and can be very useful for finding the “hot spots.” In our case, I gathered and plotted passing information from the 2013 football season and we will swap around different data sets to see what we can find.

Completed Passes

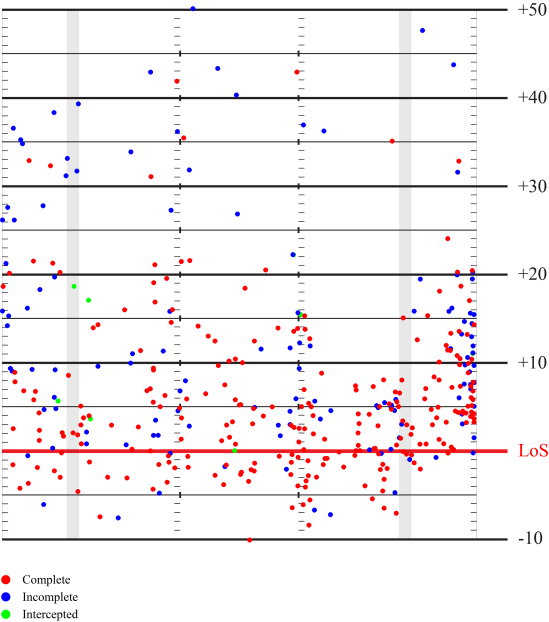

First, let’s look at the most obvious Passing Heat Map: passes complete vs incomplete vs intercepted. The diagram below represents all 392 passes that I tracked last season (not nearly as much data as the 19,000 passes tracked in the Grantland article…and my tracking isn’t nearly as precise/accurate as ESPN’s Stats and Information Group). Each dot represents one pass: red is a completed pass, blue incomplete, and green intercepted. The red line at near the bottom represents the line of scrimmage with the yard markers showing the distance relative to the line of scrimmage. The dot represents the position that the throw was to, so it does not account for yards after catch or anything of that sort. The two grey vertical bands on the left and right serve as markers to where the numbers on the field are. You can click on any of the diagrams to view a larger version.

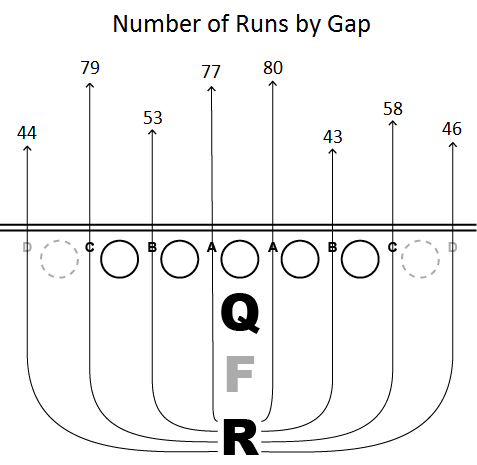

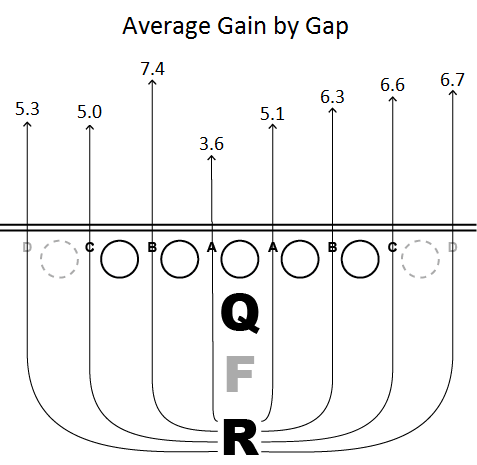

As can be seen here, the majority of passes are short throws. 68.8% of passes are thrown within 10 yards of the line of scrimmage. Only 11.5% of passes are deeper than 20 yards. These numbers fall in line with what Grantland found in the NFL.

USC also favored the right side of the field when passing. 47.6% of passes are outside the right hash mark while 29.9% of passes are outside the left hash mark. The remaining 22.5% of passes were between the hashes.

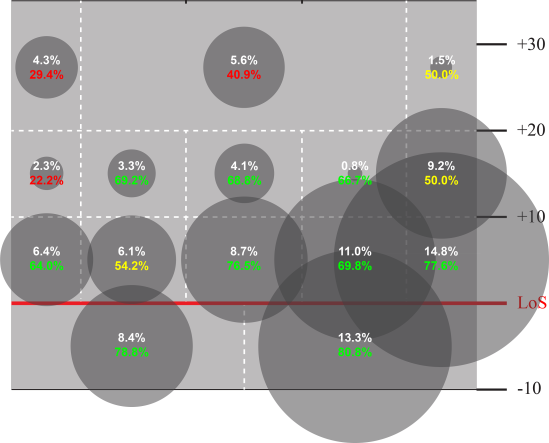

Here is the field broken down into different passing zones. The white percentages represents the percentage of passes thrown to that zone. This is also represented by the size of the circle. The colored percentages represent the completion percentages for that zone..

It is first very apparent the favored are of attack being the short right passes. Quick outs, hitches, flats, and swing passes dominate the right side in last year’s offense.

The completion rate is highest nearest the line of scrimmage and diminishes as passes get further from center. Because of the diminishing completion rate (and also probably a factor of OLine protection as well), there have been few deep attempts. There is also oddly a surprising lack of attempts made towards the intermediate passing zones on the left side of the field.

Completion percentages were highest between the hashes with a 70.5% completion rate. The right side of the field had a higher completion rate (68.8%) than the left side (57.3%).

Breakdown by Coach

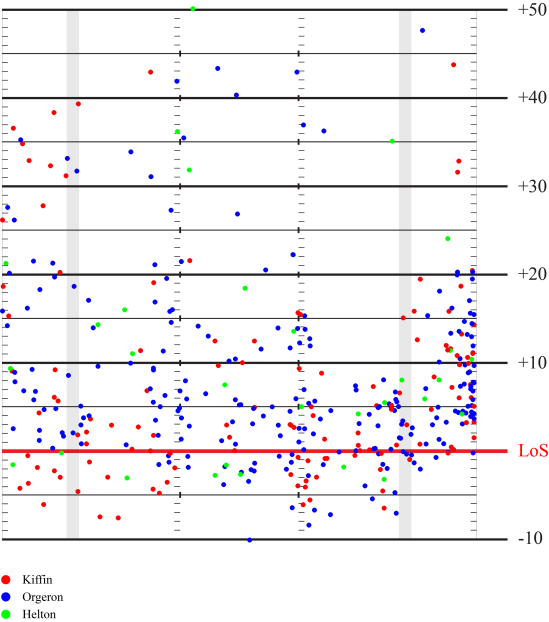

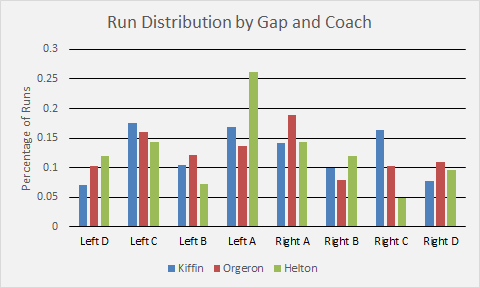

Let’s look at the breakdown by head coach. It is worthwhile to note that Coach Helton only had one game as head coach. He was also was Offensive Coordinator during Coach Orgeron’s run, so he had a hand in the play calling there as well.

Coach Kiffin had the highest percentage of passes that went behind the line of scrimmage (29.7% for Kiffin, 25.8% for Helton, and 18.9% for Orgeron). Both Kiffin and Orgeron had about 70% of their passes within 10 yards (Helton was 54.8%, but that may have just been the specific game plan against Fresno St). For deep passes beyond 20 yards, Helton had the highest percentage with 22.6% (again, possibly the specific gameplan), followed by Orgeron was at 13.5%, and Kiffin at 11.7%.

It is also worthwhile to note that Coach Orgeron was much more open to utilizing the area of the field beyond 20 yards and between the numbers (the deep middle) while Coach Kiffin avoided this space. Even Coach Helton had more attempts (5) in the deep middle than Kiffin (2) with 1/5th the amount of games.

Breakdown by Quarterback

Let’s just do a quick comparison between Kessler and the limited attempts that Wittek had based on zone. The diagram below will show the percentage of passes that went to each zone as well as the completion percentage. Kessler’s numbers are in red while Wittek’s numbers are in blue.

Kessler was much more likely to throw the short routes (69.8% of passes within 10 yards compared to 51.9% for Wittek). Wittek was slightly more likely to throw the deep ball (14.8% of Wittek’s throws beyond 20 yards compared to 11.4% of Kessler’s). There is a combination of things going on with that aspect though. Wittek was mostly put in for end game situations, so it was unlikely for him to have to throw the deep ball or else the divide may have been greater. Wittek is known for his arm though, especially compared to Kessler. Kessler actually had a greater completion percentage on the deeper balls (33% completion rate for Kessler compared to 20% for Wittek). This may have to also do with the 2nd string receivers possibly playing for Wittek.

Breakdown by Receiver

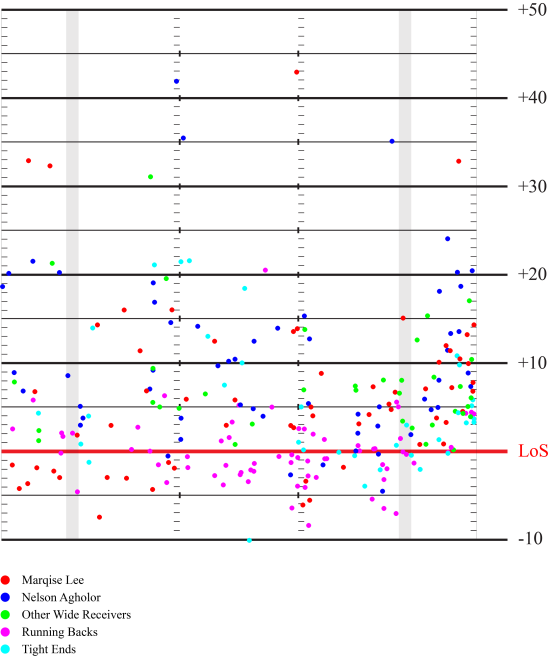

Now let us look at the receiving end of the passes. I tracked the receiver on completed passes only, so these are receptions rather than intended receivers. I have grouped it generally by position to prevent the diagram from being too cluttered. I have left Marqise Lee and Nelson Agholor separate as they were the primary targets of our passing game. By concentrating on particular colored dots, you can faintly see the passing trees and primary routes emerge.

Looking at Marqise Lee’s red dots, you can see the groupings of routes that he has caught. On the left side are a number of bubble screens caught behind the line of scrimmage. Not nearly as many bubble screens to the right, possibly indicating that Lee more often lined up on the left unless he was in the slot. In the short to intermediate depths, on the left side moving towards the middle, you can see the slant, post, and drag routes. On the right side near the sidelines, you can see the out routes and hitches.

Now let us look at Nelson Agholor’s blue dots. There are some hints of bubble screens and jailbreak screens on the right side of center. For the short passes, to the middle of the field are a number of drag routes and slants. On the outside, Agholor utilized the sidelines quire effectively.

Looking at the running backs’ pink dots shows a couple routes that are to be expected from that position. Behind the line of scrimmage are a number of screen passes found near or between the hash marks. Behind the line of scrimmage to the right are check down swing passes and ahead of the line of scrimmage are check down passes to the flats.

The Tight End routes in cyan are fairly expected as well. Mostly passes to the flats and short middle routes which are likely hitches. The deeper passes that are 10-20 yards down the field are seam routes where the TE sneaks behind the linebackers as a downfield threat. I believe the random dot 10 yards behind the line of scrimmage was Kessler was just getting rid of the ball due to pressure and just threw the ball at the TE’s feet.

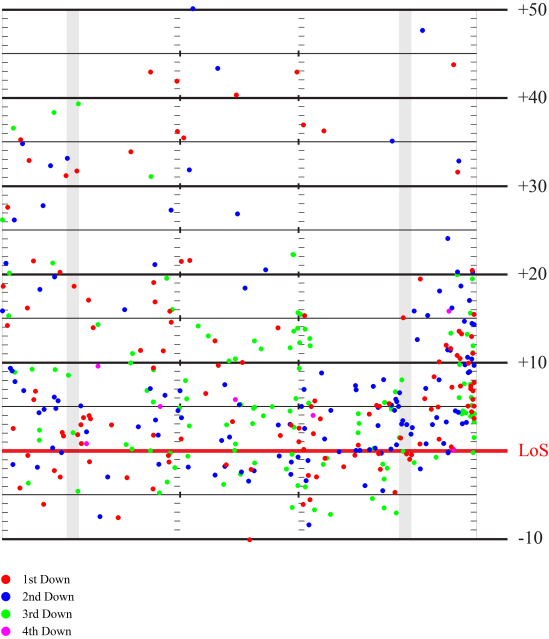

What Down is it?

Now let’s take a quick look at the heat map based on the down.

Not too surprisingly, most of the downfield passes were made on 1st or second downs. These downs also had a decent amount of short passes, typically to help make 3rd downs very manageable. 3rd downs are particularly interesting as they tend to stay within about 15 yards, so most likely the pass is made to the distance needed to convert. There are a couple down field passes on 3rd down and those are generally up the left sidelines.

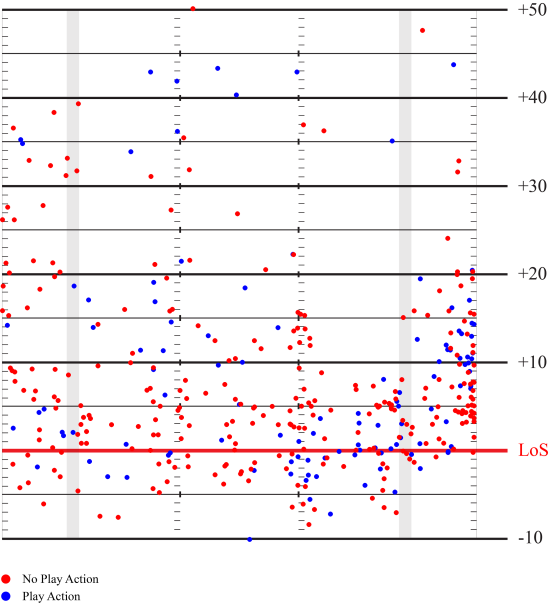

What about Play Action?

Now let us take a couple of quick looks at diagrams based on various strategies and situations. Here is the passing heat map for when USC utilized play action or not.

Most people think of play action as opportunities to take the deep pass. However, a lot of the benefits for play action come in the intermediate distances and in the flats as it freezes the linebackers. Many of the play action passes are grouped short and to the right. A good portion of these passes are probably a TE or FB leaking out from the backfield and getting open in the flats.

Overall, the percentage of short passes decreased with play action, but they were still the majority of passes. 61.9% of play action passes were within 10 yards of the line of scrimmage (compared to 71.3% without play action). 25.7% of play action passes went between 10 and 20 yards, which is a decent increase from the 17.5% of non-play action passes in this area. Deep passes were fairly similar with 12.4% of play action passes and 11.3% of non-play action passes going beyond 20 yards.

Play action passes were also more likely to go to the right side of the field, with 56.6% of play action passes outside of the right hash (compared to 43.6% of non-play action passes). This isn’t too surprising since our QBs are both right handed, so a rollout to the right is easier to execute.

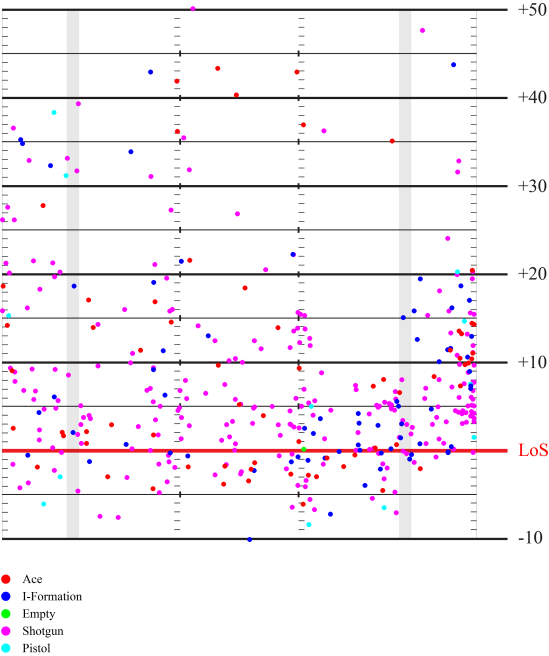

How Does Formation Change Things?

I broke it down by five offensive formations: Ace, I-Formation, Empty, Shotgun, and Pistol. Shotgun and Pistol are based on the Quarterback’s alignment. In both these formations, the Quarterback is back from the line of scrimmage with a potential running back next to him (Shotgun) or behind him (Pistol). If the Quarterback is under center (at the line of scrimmage), Ace is a formation with a single running back, I-formation is with two running backs, and Empty is no running backs. Now let’s look at how passes are made based on these formations.

On first glance, the majority of passes came out of the Shotgun formation, since the heat map is riddled with pink. This is in fact quite true. 62.1% of all of USC’s passes came out of the Shotgun. This both surprising and not given that USC spent about an equal amount of time in Shotgun, Ace, and I-Formation. This is because while in Shotgun, USC passed the ball 86.7% of the time (compared to 25% of the time for both Ace and I-Formation). Not too surprising since Shotgun is a pass heavy formation.

One interesting aspect of I-Formation is it seems to have a lot of passes to the right within 10 yards of the line of scrimmage. If you’ll reference back to the play action diagram, they share a striking similarity in that zone. I venture to guess that this is due to the I-Formation being a perfect formation to run play action out of, since it is typically a run-heavy formation. Simply do play action then dump the ball off to a TE or the FB in the flats. This has been a strong play for USC all the way back through the Carroll era.

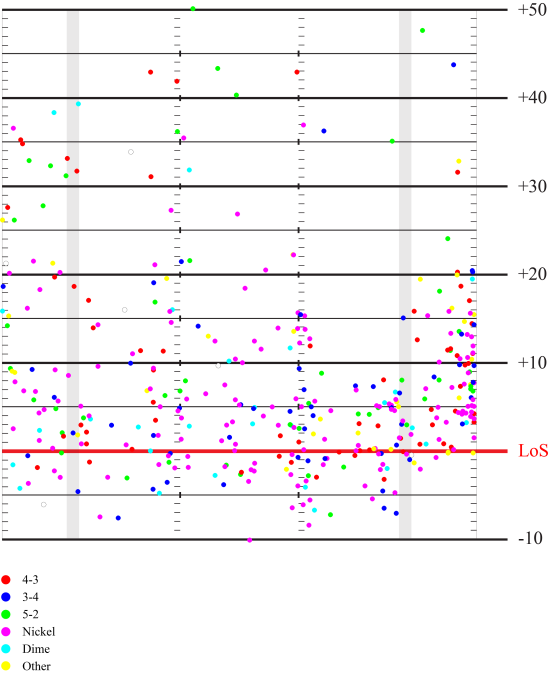

The Defensive Formation

Now to analyze how USC’s passing attack was dictated by the opposing defense. We’ll start by looking at the defensive front and work our way into the secondary. The defensive front is the alignment of the defensive players within the box. These players dictate how the run is defended and can give a clue into how the defense will react in general. The major formations that we faced were the 4-3, 3-4, 5-2, nickel, and dime. For the purposes of this article, the 4-3, 3-4, and 5-2 are similar in that they all have seven defenders in the box. The nickel removes one player, leaving six in the box while the dime removes two players and leaves five in the box. These players outside of the box are now better suited for pass defense.

One interesting thing that I note from this heat map is against the 3-4 defense. There is a distinct lack of deep throws against the 3-4 when you compare it against the 4-3 and 5-2 defenses. I am unsure about why this is and if there is an overall strategic reason for this, if it was dictated by the teams that we happened to play against that utilized a 3-4, or if it was just an anomaly.

Unsurprisingly, against the Nickel and Dime packages, our passes tended to stay closer to the line of scrimmage. Those extra defensive backs seemed to do their jobs well preventing deeper passes. Against the Nickel, there is a somewhat noticeable uptick in intermediate passes between the hashes, likely due to the lessened number of linebackers becoming spread thinner.

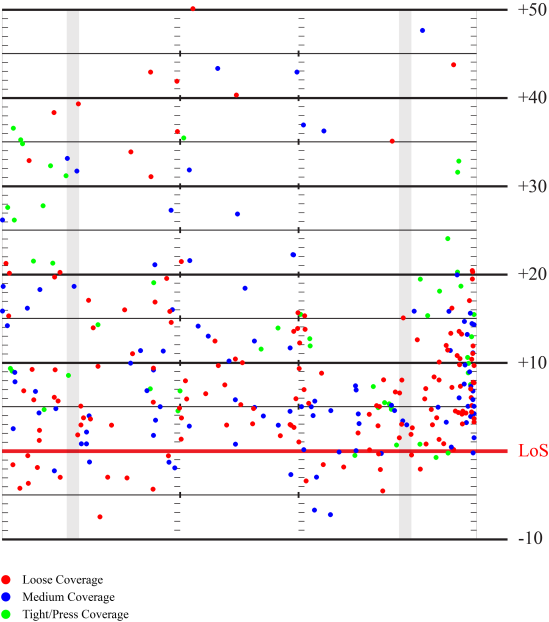

Watch the Corners

Moving further into the secondary, we have the cornerback alignment. The way I tracked this was based on the alignment relative to the intended receiver. I classified loose coverage was when the defender was seven or more yards off from the receiver at the snap of the ball. Tight or press coverage was when the defender was within three yards of the receiver. Passes to the running backs are omitted here as the secondary alignment doesn’t hold as much meaning in this context.

A good amount of the passes behind the line of scrimmage (bubble screens etc) were against loose or medium coverage. This isn’t too surprising as this allows the best opportunity for your other players to get into their blocks and also gives the receiver space to make his moves.

There are also a number of deep passes against loose coverage. On first thought, you might think that the purpose of loose coverage is to defend against the deep ball, which would imply that fewer deep passes would go to that depth. However, the loose coverage itself might imply that the corner knows there is no over-the-top help by a safety, which is why he is playing loosely. This could lead to some opportunities in the deep pass.

Against tight coverage, there is a good deal of passing to the sidelines. Most of these are probably just streaks right up the sidelines, creating a footrace between the receiver and the defender in tight coverage. The patterns crossing the middle also appear to take the shape of slant routes. This combination is interesting as it could imply utilizing both the slant and the sluggo (slant-and-go) up the sideline against tight coverage, forcing the defender to make quick turns on his hips to try to keep up.

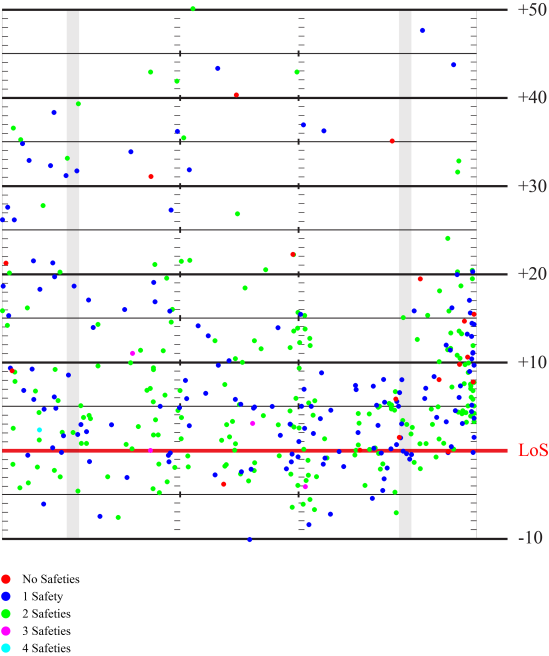

Where’s the Safety?

Moving even further back is the safety alignment. One of the QB’s pre-snap (and post-snap) reads is determining if the safeties are “even” or “odd.” This means counting how much deep safety support there is on the field. It is typical to face either one or two high safeties. However, occasionally a defense will crash all the safeties down near the box in run support or to blitz. It is also possible to see them drop three or even four guys high up top in more of a prevent defense look. I tracked the number of high safeties at the snap of the ball and charted them here.

Against one safety, there is more of a tendency towards the sidelines as you move further away from the line of scrimmage. This is usually because the safety is roaming the deep middle. Compare that against two high safeties and there is more of a cluttering in the intermediate middle of the field. This is because in a single high safety look, there can often be a defender roaming the intermediate middle zone under the high safety.

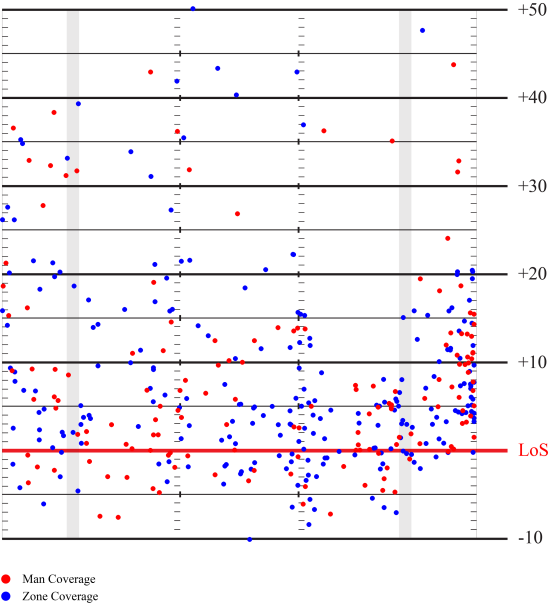

Man vs Zone

Here is a breakdown of the passes made depending on man or zone coverage by the defense.

Man coverage does appear to take the majority on a couple areas of the field including the deep right sideline and the area behind the line of scrimmage on the left. Zone coverage has other areas such as the intermediate part of the field outside the left hash as well as the middle and right passes behind the line of scrimmage. Note that many of these passes behind the line of scrimmage in the middle or right side of the field are to the RBs, so they may be checkdowns after the receivers could not get into open areas from the zone coverage. Overall, passes against either man or zone coverages were fairly balanced around the field.

As a side note, Kessler had a slightly higher completion percentage against the zone (68.3%) compared to against man coverage (61.6%).

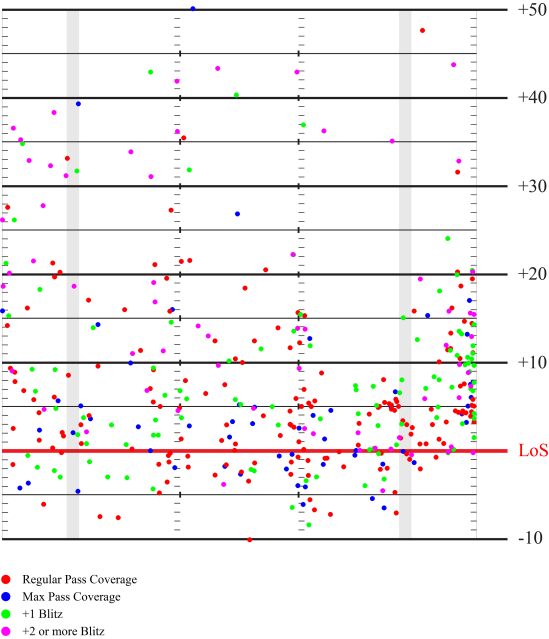

Bring the Blitz

Finally, let’s look at the last breakdown for passing heat map that I will do today: passing against the blitz and passing against max coverage. A typical pass rush is four defenders going after the QB. This leaves seven defenders in pass coverage. Bringing extra pass rushers can force a bad throw, but it can also leave the field open for passes due to the reduced coverage. On the flip side, dropping extra defenders into pass coverage can leave the QB with no open targets, but the reduced pressure can give the QB and receivers enough time to find a gap in the defense. Let’s take a look.

Against max pass coverage, meaning at least eight defenders defending the pass (leaving three or fewer pass rushers), USC typically threw the ball short. It was usually just a check down, which is fairly expected since most receivers will be double covered.

Now for the blitz. Against a +1 blitz (five pass rushers, six pass defenders), USC still spread the ball around the field fairly well. There were a number passes up either sideline but also kept it around the short middle of the field as well. The +1 blitz is interesting because it is five pass rushers against at least five blockers in the offensive line, so it is fairly balanced still. For the +2 or more blitz, there are at least six pass rushers, which means that either the running back and/or a TE must block or there will be a free rusher. Against the +2 blitz, you see fewer passes to the short middle of the field, mostly because the RBs and TEs are likely tied up in blocking. There are, however, a number of deep passes against the +2 blitz. If the pass rush fails to get to the QB, it opens up for one-on-one situations deep since there is most likely no safety support.

Let’s look at completion percentages in these situations. With the standard seven pass defenders, USC completed 71.4% of passes. With max coverage, this increased to 73.2%, so Kessler can be patient and wait for his receivers to get open or to check down. Against a +1 blitz, USC completed 60.2% of passes, so noticeably down. Against the +2 blitz, USC was down to 53.1% completion rate. The blitzes were fairly effective in that sense.

Conclusions

That’s all I have for now. I did gather data for specific coverages that were used, but did not really have the time to create the diagrams for those. Maybe I will still create them if I have time later on, but I would expect that this will be my last post before the 2014 season starts. I look forward to see how this data changes under Coach Sark. I hope you all found this data useful and interesting. I also hope to see you all return for more analysis of the 2014 USC Football Season.